The Spy Who Killed: Investigating MI6's wartime wife killer

How Britain's spooks launched a cover-up when one of their own went rogue

PART ONE

The date was April 10, 1941. Within the space of forty-eight hours, Germany would capture Zagreb, and then Hungary would join the wider invasion of Yugoslavia. It marked the beginning of another bloody chapter of the war, one that left hundreds of thousands dead.

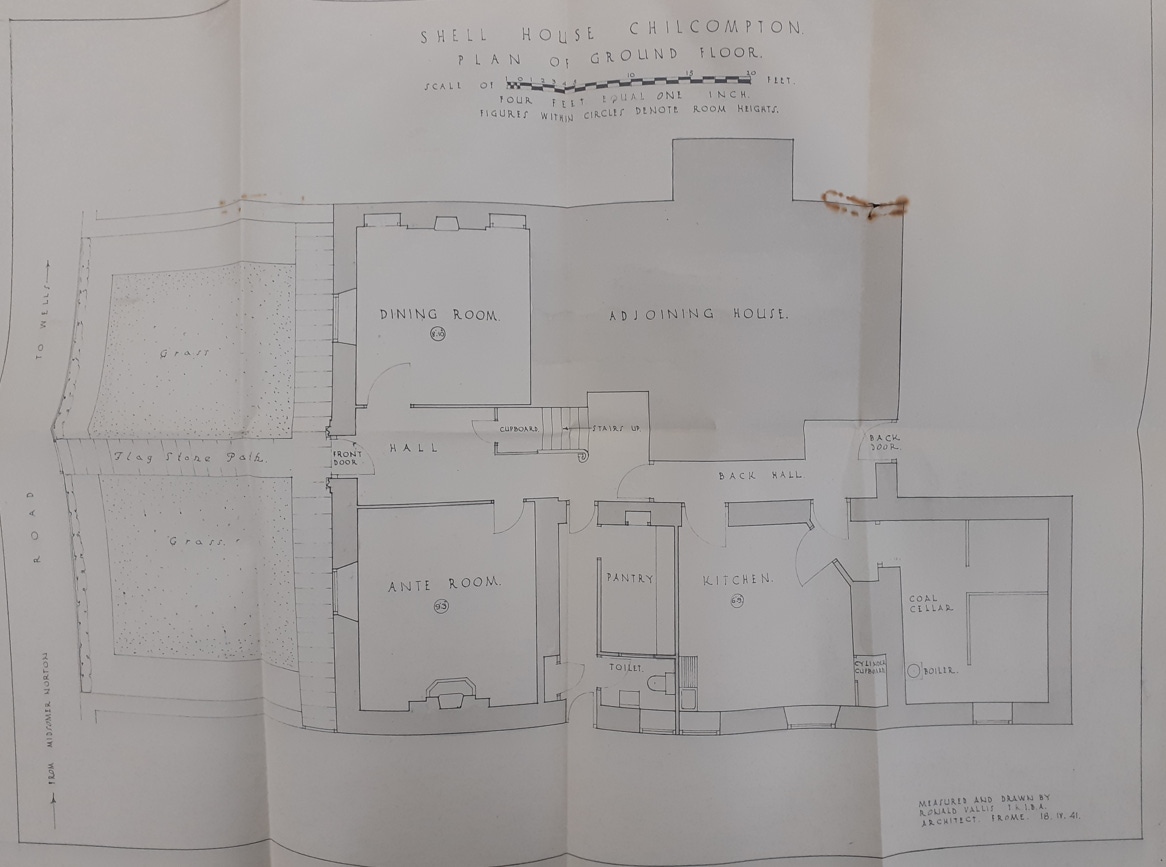

It all seemed a million miles away from that bright Spring morning in the picturesque Somerset village of Chilcompton, where half a dozen Army officers gathered to bid farewell to a friend moving on to pastures new. Drinks were imbibed, photographs taken in the garden, and soon lunch was being laid out in the officers’ mess — the dining room of an attractive country cottage assigned as a billet for soldiers planning the defence of Britain from an anticipated German invasion.

But as the men sat down to eat, none of them heard two revolver shots ring out from a room across the hallway, shots that would push Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), otherwise known as MI6, into launching an unprecedented cover-up.

Located in the Mendip Hills, some two miles from Midsomer Norton, Chilcompton is an old farming and mining village with a population of some two thousand people. Back in 1941, it housed soldiers from, amongst others, the 2nd Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment, which was used as part of the British Expeditionary Force and evacuated from Dunkirk in 1940. The scene of the crime was the village’s eighteenth-century Shell House, location of the officers’ mess, and its two main protagonists a married couple who lived close by, in a cottage named The Woodlands, and who would have taken a keen interest in the contemporary events in the Balkans — Major William Mackinnon Gray and his wife, Helen Amaryll Gray, known as Ryll.

Ryll was born in Hungary in 1906. Her maiden name was Balkany, lest there be any doubt about her family’s long connection to the region. She married her husband — and as it turned out her eventual killer — in 1936, after meeting him in the Bulgarian capital Sofia, where he was on a ‘diplomatic’ posting.

The day of Ryll’s death, Gray was handing over control of B Company to Captain David Dobie, himself a Dunkirk veteran who would go on to play a leading role in Operation Market Garden, the Battle of Arnhem, and be immortalised in the TV series Band of Brothers.

Exactly why Gray was leaving his company behind at Chilcompton is still unclear. He suffered from ill health, bought about by a case of malaria. According to later court testimony, Gray was to take charge of a less demanding unit. Dobie later found the company’s accounts short by £100 and Gray himself admitted handing over cheques to fellow officers that he knew would bounce. He had a long history of money problems and it’s possible that some financial mismanagement had already been spotted and he was being moved on for that reason. Gray also, it appears, had a serious drinking problem.

On the morning of the shooting, Gray failed to arrive for breakfast at the mess as usual. His batman, Private William Bryant, found Gray and his wife still in bed asleep at 10am. They had stayed up well into the early hours, drinking and discussing their money problems. Bryant knew the couple well and liked them. He described them as being on “very affectionate terms” with each other, and he was more than happy to help them out. For example, later that morning a Major Farrell called at the house, but Gray told Bryant to say he wasn’t in. Gray eventually dragged himself out of bed and told Bryant to send a telegram to an address in Poole. “Both arriving this evening,” it said. Gray then went to take charge of his final company parade.

Meanwhile, Bryant helped Ryll to pack. But at noon she sauntered into the kitchen where he was eating lunch, appearing “slightly merry, but not drunk”. Bryant continued with his tasks but didn’t see either of them again until 3pm when, needing advice on where to pack some official papers, he headed over to Shell House. There he ventured into the anteroom of the officers’ mess and found Gray and his wife both apparently lifeless and covered in blood, Ryll reclining on a sofa and Gray sat stock-still in an armchair.

This was the horrific and unexpected aftermath of Gray’s farewell party. Only a handful of officers had been present, David Dobie among them, as well as Second Lieutenant Samuel Wright-Flint. The group had originally planned to meet at 12.30pm, but Gray kept them waiting until 1.45pm. When he eventually turned up, Ryll was with him. According to Dobie, she had clearly been drinking, while Gray appeared sober. The friends had “a drink or two” in the anteroom, before going into the garden, where Dobie took photos. He and the other officers went off to lunch at 2.30pm, leaving Gray and Ryll alone in the garden. Gray said he would catch them up.

But it was Bryant who was next to see them, about thirty minutes later. He ran off to alert Dobie and the others, none of whom had heard the gunshots. (A couple of days later, an experiment was run in the anteroom, with a police officer firing two shots from a .38 revolver, to ascertain how far they could be heard. A faint thud was heard in the dining room, but nothing of the second shot).

Dobie noticed blood on the top of Gray’s head and heard loud snoring or heavy breathing. He also noticed a wound on Helen’s head but took it to be a bruise, incurred during a “domestic”. There were no other signs of a struggle.

Dobie went off to call an adjutant but when he returned he was surprised to see Gray standing at the far end of the room, with a revolver in his hand. As Dobie entered, Gray began to raise the weapon, and Dobie, by his typically cool account, “rather hurried the last few yards”. As Dobie approached, Gray broke the revolver and four rounds fell to the floor, including two empty cases. Dobie took possession of the gun.

At this point, Dobie noticed both Gray and Ryll had more serious wounds than he’d first observed and went to call a doctor. When he returned, Gray was sat in a chair and Wright-Flint was jotting down what he said. Gray muttered something about letting them all down, and also spoke about taking money, admitting that he was “financially and physically broke”. As Dobie put it: “He also mentioned his diplomatic work, the Foreign Office.”

Most of Wright-Flint's contemporaneous notes have never been published until now. Much of it was rambling and incomprehensible, but Gray admitted: “I have done you out of £100.” As one man checked his pulse, he muttered: “Get your bloody thumb off.” Gray also complained about the clock being slow and blithely murmured: “I have blotted my copybook today.” When another officer, Captain Styran, entered the room, Gray told him: “Styran old boy, I have shot Ryll and then myself, I’m broke. I have let Keating down and you. My .38 is always loaded, bring it here. I have swindled you, the Colonel...I’m broke financially, utterly and completely broke.” He went on, saying how: “Ryll and I came back from Hungary. We were allowed officially £6. I went into Airways as a salesman.” He also said: “I was employed by the Foreign Office and sent to Istanbul. Doctor where are you? Where is my wife?” At this point, Gray was carried away by the ambulance men, clearly delirious but also in the mood for confession.

The extent of Gray’s wounds have never been made clear, neither in contemporary newspaper reports nor in the declassified portion of the case papers held in the National Archives. We do know that Gray was taken to the Royal United Hospital in Bath, where he survived. Ryll was taken to the hospital in Paulton, where she regained consciousness but died at about 4.30pm. She had been shot on the right side of the head, about midway between the ear and the eye. The wound was small and dark, and surrounded by a circle of powder burns, suggesting that the muzzle had been pressed against her head, or at least fired from a very close range. There was an exit wound on the other side, behind the left ear. The cause of death was found to be laceration of the brain, some of which was found poking through the exit wound. In the anteroom, police found a bullet hole in a cushion and another in the ceiling. A bullet was later found below the floorboards of an upstairs room, judged to have entered at a 45-degree angle. This, it would appear, was the bullet Gray had fired at himself.

At the hospital, Gray was cautioned and made a voluntary statement. He said: “I’ve shot my wife with a .38 revolver. If I had not done what I ought to do I should have had to face arrest and be placed under court martial. How is my wife? Has she stopped breathing? Let me have my revolver, I want to show you that two chambers have been fired.” When asked who fired them, he replied: “I did.” When asked why, he answered: “Financial embarrassment.” Gray fell silent for a minute then added: “Constable you make a note. I shot myself through the head.” Another two minutes passed, and he spoke again. “Constable, I don’t want to be saved. I want to die. I have committed a crime, two crimes.” Gray was incapable of signing his statement.

Gray was later charged with murdering his wife, and attempting to commit suicide — an unusual charge even then, which read in full: “[He] unlawfully did shoot with a certain revolver at and against himself with intent thereby then feloniously, wilfully, and of his malice aforethought, to kill and murder himself, against the peace of our Lord the King, his crown and dignity.”

After the shooting, police found pawnshop tickets for a gold watch and other items in Gray’s room, as well as several unpaid bills, totalling some £338. As the prosecutor at his trial later put it: “Major Gray made it quite clear that his financial position was quite deplorable.” But little else of note came out at trial.

One of MI6’s most senior officers saw to that.

PART TWO

William Mackinnon Gray was born in Bayswater, London, on January 28, 1902, to a well-to-do father William Mackinnon Gray and mother Elizabeth Paul Munro. He joined the Army in 1923 and married his first wife, Edith Barbara Stephenson, in Colchester in July 1926. She was a Yorkshire lass born in Beverley in 1903. According to his official career history (as disclosed at his trial), Gray spent eight years in Egypt, where he contracted malaria, which afterward seemed to recur once a year. According to their divorce papers, the couple had lived in Istanbul together. The couple had a son, also named William Mackinnon Gray, born in 1931. They divorced in 1936, a few weeks after Gray was caught committing adultery with a woman named Frida Kandler at the Charring Cross Hotel, apparently as part of a much longer relationship which had begun overseas. According to the divorce papers, Frida Kandler lived with Gray at 7, Rue Oborischte, Sofia.

Newspaper reports of the trial told how Gray was attached to the Foreign Office up until 1937 and was stationed in Bulgaria when he retired from the Army that year, before being placed on the officer reserve list. But that was only part of the story. In fact, Gray had been MI6’s head of station in Sofia, posing as a passport control officer. He had joined the service in 1932, received training in Istanbul and took on the role of ‘assistant’ in Jerusalem.

While MI6, unlike MI5, has never declassified any of its files, and is unlikely to do so, the historian Keith Jeffery was given limited access to the archives to write his official history of the service. In his book, MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909-1949, he details how the Sofia station had a particularly high turnover between the wars. Charged mainly with keeping tabs on Communist subversives, from 1920 until the war there were six heads of station, who all operated under cover of Passport Control Officer.

Jeffery did not shed much light on Gray’s activities in Sofia, but noted that he had succeeded the “distinguished personage” of Engineer Captain Charles Limpenny (who served from 1933 to July 1935), an old friend of C’s, Sir Hugh Sinclair. Limpenny was recalled to London to take over as head of the Economic Section, having made a success of his posting.

As Jeffery wrote:

The same could not be said of his successor, Mackinnon Gray, who had been introduced to SIS in 1932, and had spent some time as a ‘learner’ at Istanbul and an assistant at Jerusalem before his appointment to Sofia. Gray had a problematic personal life. In 1936 his wife sued for divorce, and there was concern that his SIS appointment might get mentioned in the proceedings. Situations like this, when crises in the private lives of officers (and, indeed, agents) might jeopardise cover or security generally, were not uncommon, though in this instance — and to his evident relief — Gray’s real role in Sofia remained secret.

However, the divorce was the least of Gray’s problems. During the early part of 1937, concerns were raised about “financial irregularities in the payment of an agent”. C ordered an inspection of the Sofia office and sent Limpenny back to his old stomping ground to investigate. He found, perhaps generously, that Gray was “guilty of carelessness and slipshod record-keeping rather than peculation” but the matter seemed to put an end to his career. As Jeffery wrote:

[The incident] throws revealing light on the mechanisms by which a local SIS station ran its finances. While there were strict rules that any local expenditure had to be approved from London (which Gray had failed to follow), funds appear routinely to have been transferred from Head Office to the head of station’s personal bank account and from there to a second offshore account. In Sofia local currency for paying agents was acquired clandestinely on the ‘Black Bourse’ by the wife of a junior member of the Passport Office staff.

Given the limited details about the case, it’s open to interpretation whether or not Gray left MI6 of his own volition or was nudged out the door. But in September 1937, Jeffery says, Gray “abandoned his post, returned home without authorisation and resigned from the Service,” leaving Limpenny to make good some bounced cheques.

Gray married Ryll in Sofia the same year. The relationship was described in court as a “love match” and they were said to have had an “extremely happy married life”. After officially leaving the Army, Gray bought a farm in Hungary and put all of his money into it, except for £150 he had invested in England. The couple lived on the farm until the Munich Agreement of 1938, which handed Hitler the Sudetenland. In short order, Gray received a telegram from the British Consul ordering him to return to England. He sold up almost immediately and headed back to Blighty.

Why was Gray so profligate? People often steal from their employer to feed some sort of addiction. Gray might have been stealing to buy alcohol, or even just to fund a nice lifestyle for himself and Ryll. We will probably never know, but whatever underlying cause was at the root of his dodgy financial affairs, it evidently continued back in Britain. He was not initially allowed to re-join the Army and tried to scrape a living as a door-to-door salesman, but he was not particularly successful and the job only seemed to land him in further debt.

After hearing that Gray had murdered his wife, renewed consternation pulsed through the upper echelons of MI6. Its vice-chief and head of counter-espionage, Valentine Vivian, was dispatched to Somerset for a “damage limitation” exercise. Fearing that Gray’s secret service work might be exposed, he had little trouble convincing Somerset’s Chief Constable to excise any reference to ‘Passport Control’ or his previous career from the legal proceedings. Indeed, the trial was brief and the depth of reporting shallow, suggesting that journalists might also have been nobbled.

Furthermore, no photograph of Gray emerged, suggesting that Vivian might have persuaded Dobie to destroy the negatives of the photos taken shortly before the murder. Whatever the extent of Vivian’s cover-up, it was an extremely rare intervention and was clearly motivated by the potential embarrassment the case would have caused the service.

As Jeffery summed up the case:

[Gray] evidently had a difficult and troubled private life. There is no way of estimating the extent to which (if at all) the pressures of secret intelligence work may have exacerbated his personal problems, though one may reasonably suppose that the strains of having to maintain a secret professional existence may not have helped. What is clear from this case, however, is that domestic crises, of whatever sort, had an unsettling potential to go public and endanger operations. Thus the Service took these kinds of problems very seriously indeed.

It would probably have suited MI6 if Gray had succeeded in taking his own life, or at least been declared unfit to stand trial. But a doctor who examined him at HMP Bristol before the trial found him to be an “intelligent man” with no evident “mental disorder”. He had behaved well and was quiet, with no signs of deterioration. Gray described his father as being given to “alcoholic excess” but reported no ill-treatment by his parents. He never felt that he had “suffered from any condition that could be construed as insanity”.

Prior to the shooting, Gray had experienced no memory problems. However, he claimed to have “complete amnesia of his acts”. He remembered everything up to the time of saying his farewells to the company sergeant major and the quartermaster sergeant. Then he claimed to remember nothing until he woke up in a hospital room. The doctor doubted this account. “In view of the bullet wound in his head probably damaging at least the meninges of the brain, the traumatic unconsciousness after the act was to be expected,” he wrote. “But I suggest that the sudden amnesia just prior to the act does not constitute a definite clinical entity, in view of the clearness of his history as related to me, and his easy recollection, even of small events.” The doctor found that Gray knew what he was doing at the time and was fit to stand trial.

Vivian’s cover-up went off without a hitch, although in its report of the trial the News of the World reported that Gray once “did special work for the Foreign Office”. Gray pleaded insanity. In court, it emerged that William and Ryll had spoken well into the early hours about their “serious financial position”. Gray told his wife how desperate things were financially, and when asked in court what would happen to her if he were to die, he replied: “She would have been left in a serious position.” When asked if they habitually drank a lot, Gray replied: “A little, but not out of the ordinary.”

The prosecution alleged that Gray had stolen money to cover a £300 debt, partly accrued by his wife’s medical bills (she had twice tried to commit suicide). He denied that the pair discussed suicide as a way out of financial woes.

On July 15, 1941, the jury took just twenty minutes to find him guilty. Within the hour, at just thirty-nine years old, Gray had been sentenced to death. Gray was described during his trial at Winchester Assizes as being a “slightly-built man of medium height”, who calmly gave evidence, but who “turned very pale when sentence of death was passed”. The jury made a strong recommendation to mercy, but Gray was still placed in the condemned man’s cell at Winchester Prison while the Home Secretary made his decision. Thomas Pierrepoint, the uncle of Britain’s most famous executioner Albert Pierrepoint, agreed to carry out the sentence on a provisional date of August 5, at 8am.

Gray apparently remained quite calm during this period, but in any case the sentence was officially commuted to life on July 31, although the prison apparently did not receive this notice until the following day, with just over a week to go. This was ratified by a court order on August 12, 1941, when the Honourable Sir Ernest Knight, of the King’s Bench Division, ruled that Gray must be “kept in penal servitude for the term of his natural life”.

But that is not what happened.

PART THREE

It was always possible to work out that Gray was released because records show that he died on June 19, 1975, at the General Hospital in St Helier, leaving everything to his third wife, Patricia Frances Gray, or, in the event of her imminent death, their son, Richard Duncan Alistair Gray.

But how long he actually served was a mystery - until now.

Gray’s prison file was not due to be made public until 2049, meaning details about when, why, and under what conditions he was freed, would remain hidden. However, after a four-month wait, they were released following a Freedom of Information request, in which it was pointed out that publication could do little harm as almost everyone involved in the story was dead.

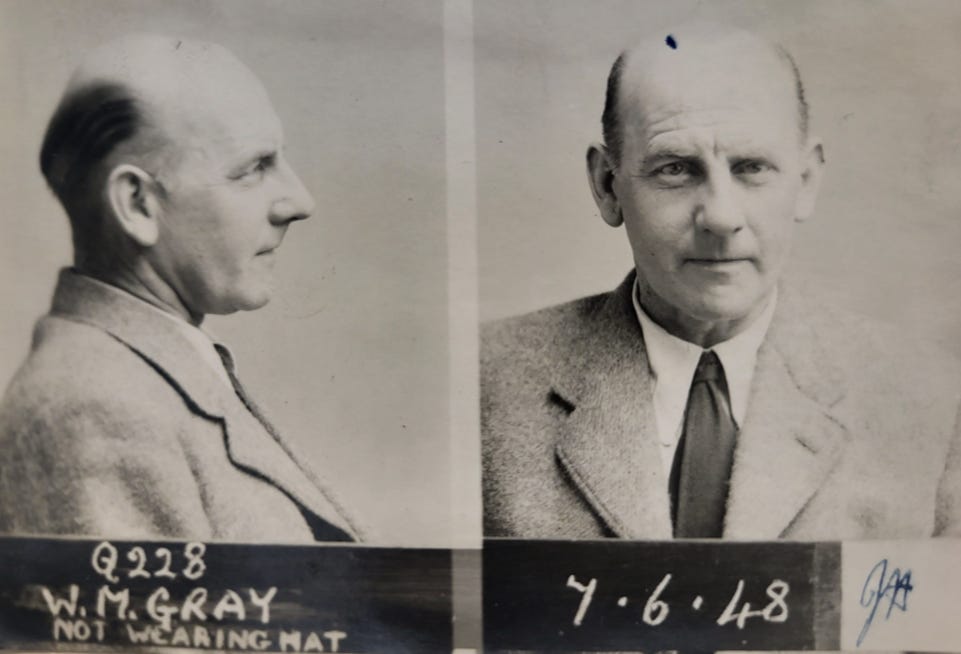

In addition to two sets of prison custody photos, the first known photos of Gray to emerge, the files also contained a further startling revelation - the killer was released after just seven years to live his life in exile.

During his prison years, Gray made numerous petitions to the Home Secretary, Labour’s James Chuter Ede, and although the contents of his appeals are not contained in his file, his date of release is - July 8, 1948.

The decision was made despite evidence that he had not truly atoned for his crime.

In February 1946, a doctor who had seen him shortly after the crime and then again more recently, remarked that Gray had begun referring to the incident as a “suicide pact”. With the doctor stating that there was “no doubt in my mind that there is no true amnesia in this case,” he also found it “extremely doubtful” that there had been a suicide pact. In April 1946, the governor of Isle of Wight prison wrote to the Home Office to explain that Gray had once again changed his story. He now accepted that he killed his wife because he could see no way out of the financial mess. “He could not, he says, leave his wife alive as she would be penniless and friendless in this country. So he shot her and then attempted to take his own life,” he wrote.

But overall opinions of Gray were high. In October 1947, another prison doctor found him to be “most cooperative and very reliable and trustworthy”. “The more one sees of this man, the more favourably impressed one becomes and the more confident in his future. He is philosophical about the past, and looks to the future with quiet confidence and free from any anxiety, or self-recrimination. His ethical standards are high.” Several prison chaplains also gave him positive references.

The files show that Gray inherited a significant sum of money from his mother while imprisoned, and the authorities felt this would help him greatly. He also had a very good prison record, with only one minor allegation of misbehaviour against him, and even that had been dismissed. Gray took on numerous jobs, including in the library and later in the officers’ mess, no doubt the bitter irony being totally ignored. While she was still alive, Gray said he wanted to live in Australia with his mother. Later, he vowed to move to South Africa. He received several visits from his sister and her husband, as well as from a female friend, Vilma Perl. He also received many letters. Intriguingly, one came from a man in Budapest with a Bulgarian name, described as an uncle.

The final decision appears to have been made on January 19, 1948, when the Home Office wrote to the governor of Leyhill prison, stating that the minister had decided to release Gray on license when he had completed seven years of his sentence. No detailed reasoning was given. The Home Office stated that it had no objection to Gray moving to South Africa, and he was given permission to write to the embassy for a visa.

There are some tragic postscripts to the case.

Gray’s first wife, Edith, remarried to a Major Ian Bruce Fernie. In June 1943 she changed their son’s surname by deed poll, from William Mackinnon Gray to William Mackinnon Fernie. Edith died the next month, and her son died in 1965, ending the family naming tradition for good.

After his release, Gray moved to Beaulieu, Hampshire, before finally settling in a cottage on the island of Jersey. Gray’s sister, Jean Milne, had already moved there with her husband Ewan Mitchell Milne. Milne’s son from his first marriage was the political philosopher Professor Alan John Mitchell Milne, who was blinded by a sniper’s bullet in Germany in the spring of 1945. So the family included two men who had survived a gunshot wound to the head — one a hero, one undoubtedly a villain, albeit one with charm and friends in very high places.